One Man, One Bike, One Epic Ride

The World According to Michael Ruegg

If you’ve ever dreamed about throwing a leg over your motorcycle and just riding until the road ran out, Michael Ruegg has already lived your dream—and then some. Back in 1985, while most university graduates were brushing up their resumes and preparing for the corporate grind, 22-year-old Michael Ruegg had a different idea. Fresh from completing a degree in Agricultural Science, Michael looked at the world—and his Yamaha XV750 cruiser—and thought, Why not? "I didn’t want to work, so I went for a ride," he said in the most understated fashion.

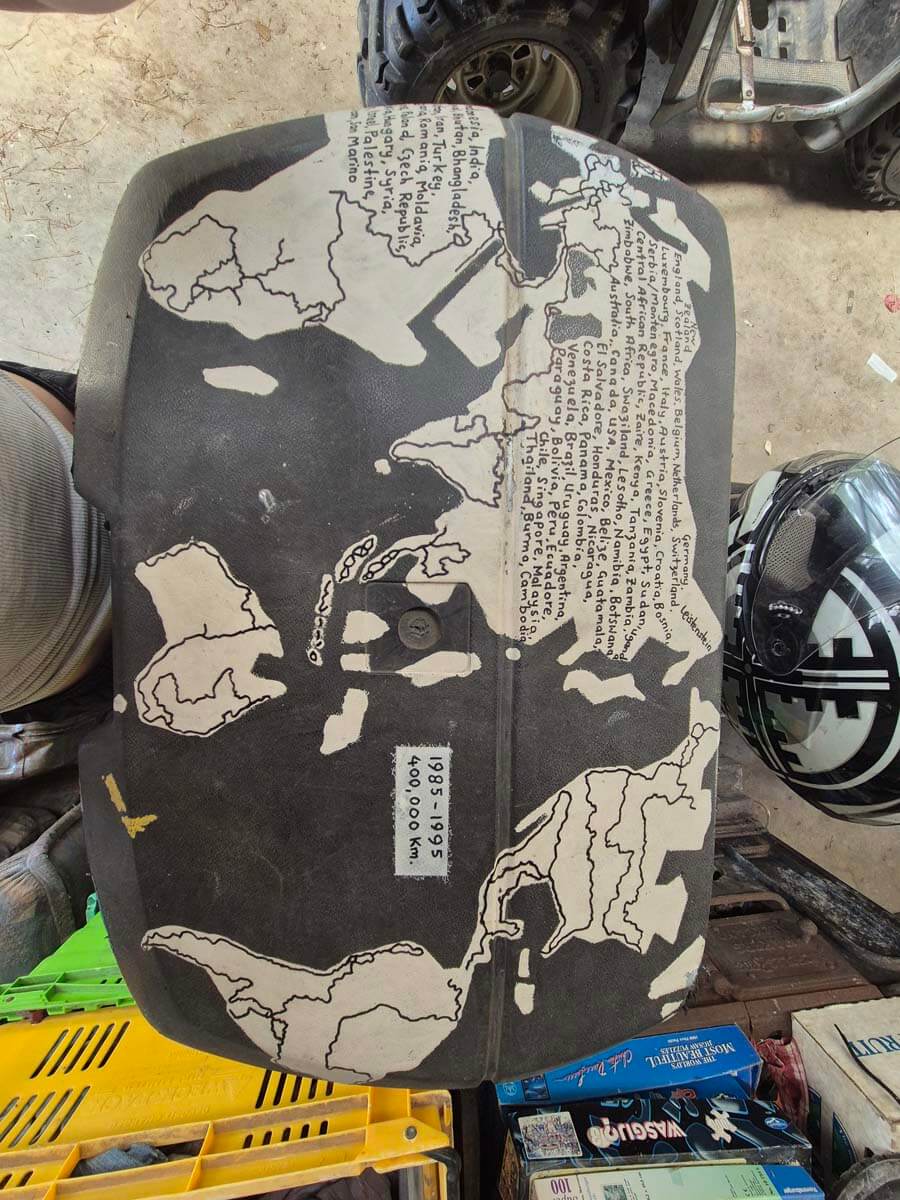

What followed was an extraordinary seven and a half year journey that saw him circumnavigate the globe solo, long before the era of GPS, mobile phones, or travel blogs. Armed with a tent, a few tools, and an adventurous spirit, Michael set off with no plan, no route, no destination, and no return date. Just a man and his motorcycle against the world.

-

Michael bought his Yamaha XV750 in 1981 from Smiths Scooter House in Tauranga, New Zealand. Prior to that, he’d owned a Yamaha XS500E but wanted something with more grunt. "At the time, the XV750 had one of the fattest rear tyres of any bike on the market," he says. "The V-twin engine totally dominated the visual aspects of the bike. There was nothing like it on the market at the time. How could I say no?"

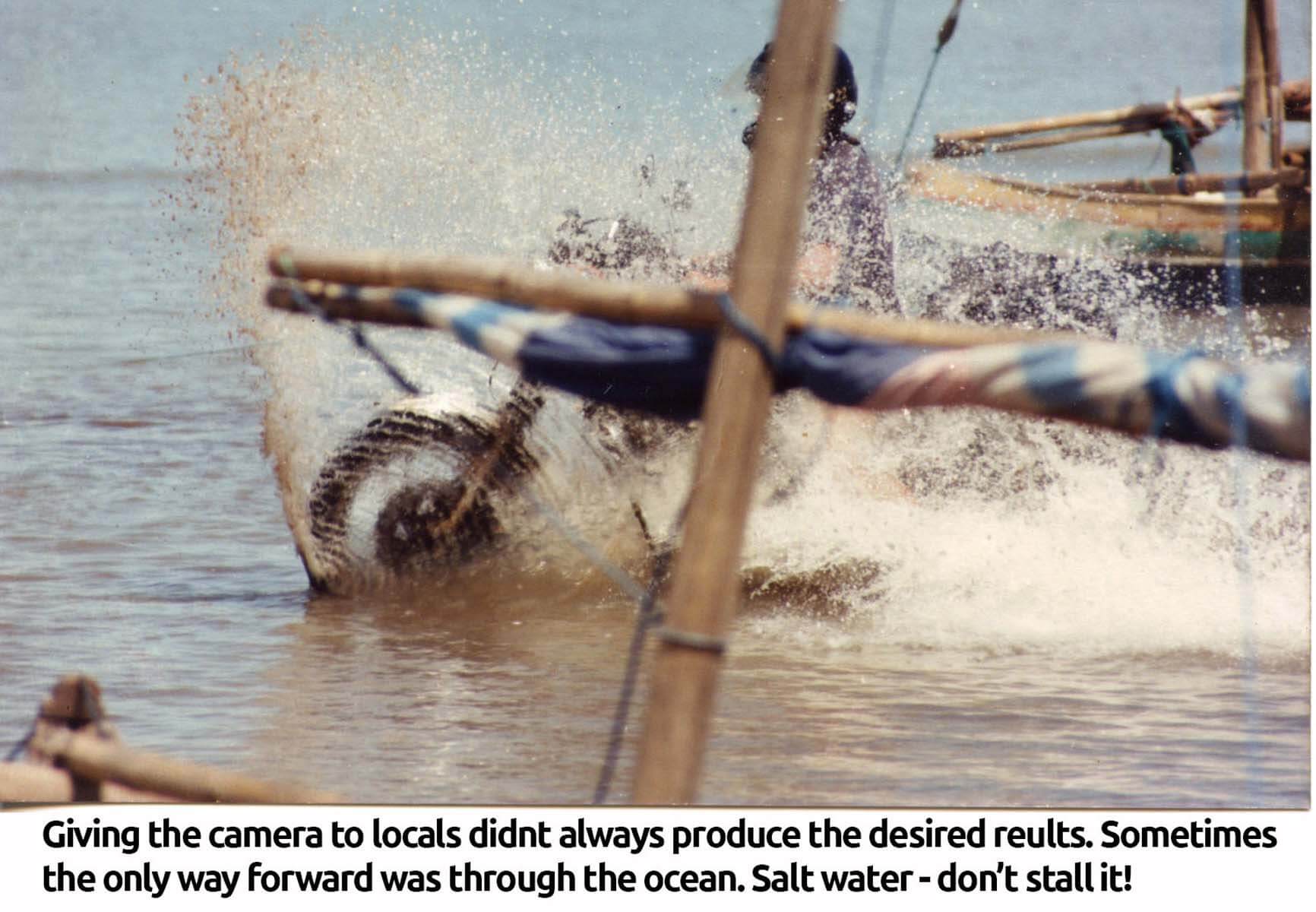

The XV750 wasn’t built for long-distance global travel, but that didn’t stop Michael. "It was what I had at the time, so it became a globe-trotting machine," he says. He strapped on jerry cans that expanded the fuel capacity by an additional 55 litres, swapped out the tyres for something more rugged, added some spare parts and basic tools and a tent - and that was it. He was ready to see the world.

The journey began with a one-way shipment of the XV750 to England. "To be truthful, I just wanted to go for a ride, and England on the XV750 seemed like a good idea," Michael recalls. "It was never meant to be an around-the-world trip. I didn’t even have a plan. I just arrived and started riding."

After a year of winding through the continent, the journey took an unexpected twist. Michael decided to find his great aunt, a nun who had disappeared into the depths of Africa during a time of civil unrest.

"She had been working in the Belgian Congo, but with the only phone in the area belonging to the military and the postal service being patchy at best, no one really knew where she was," Michael explains.

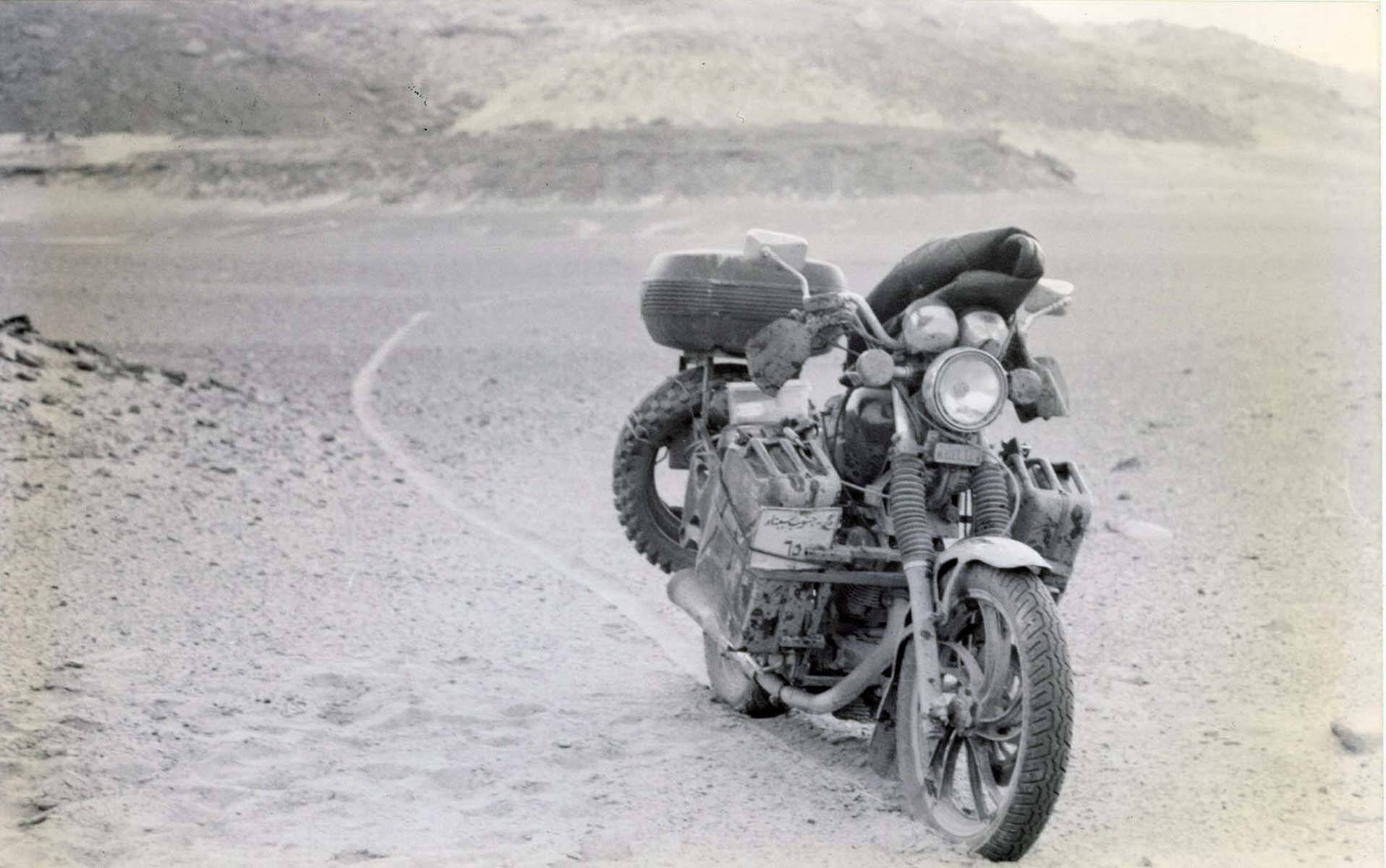

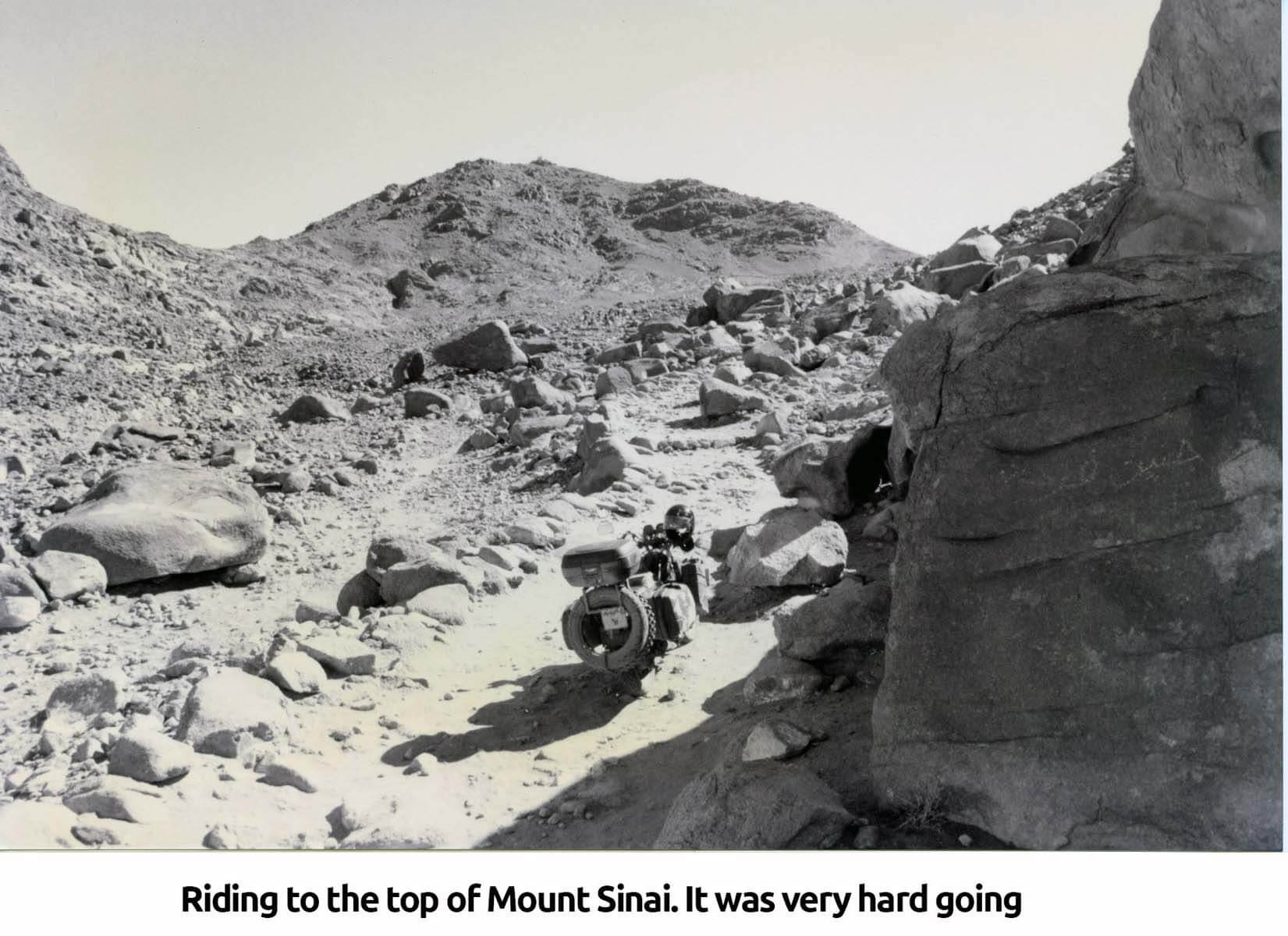

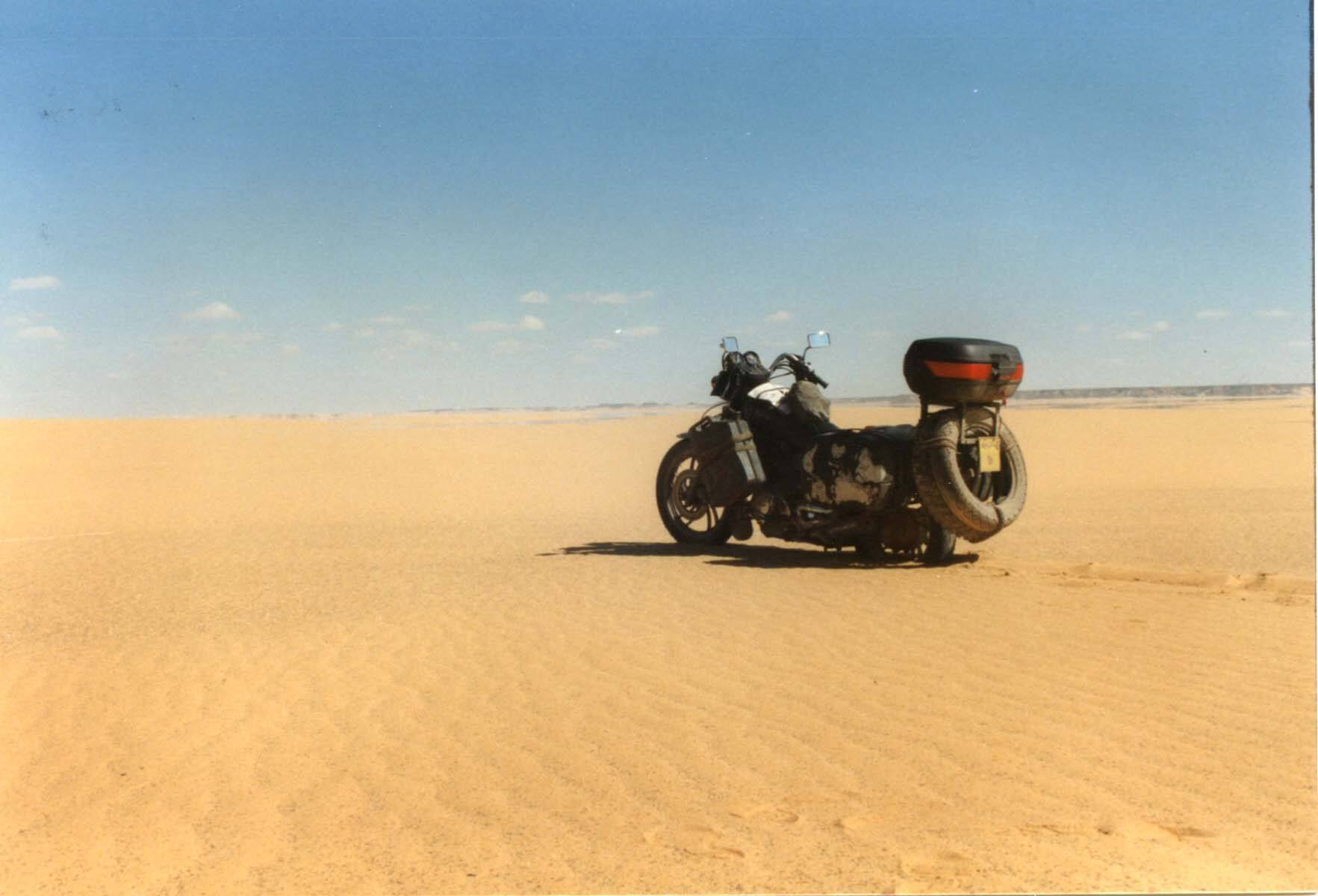

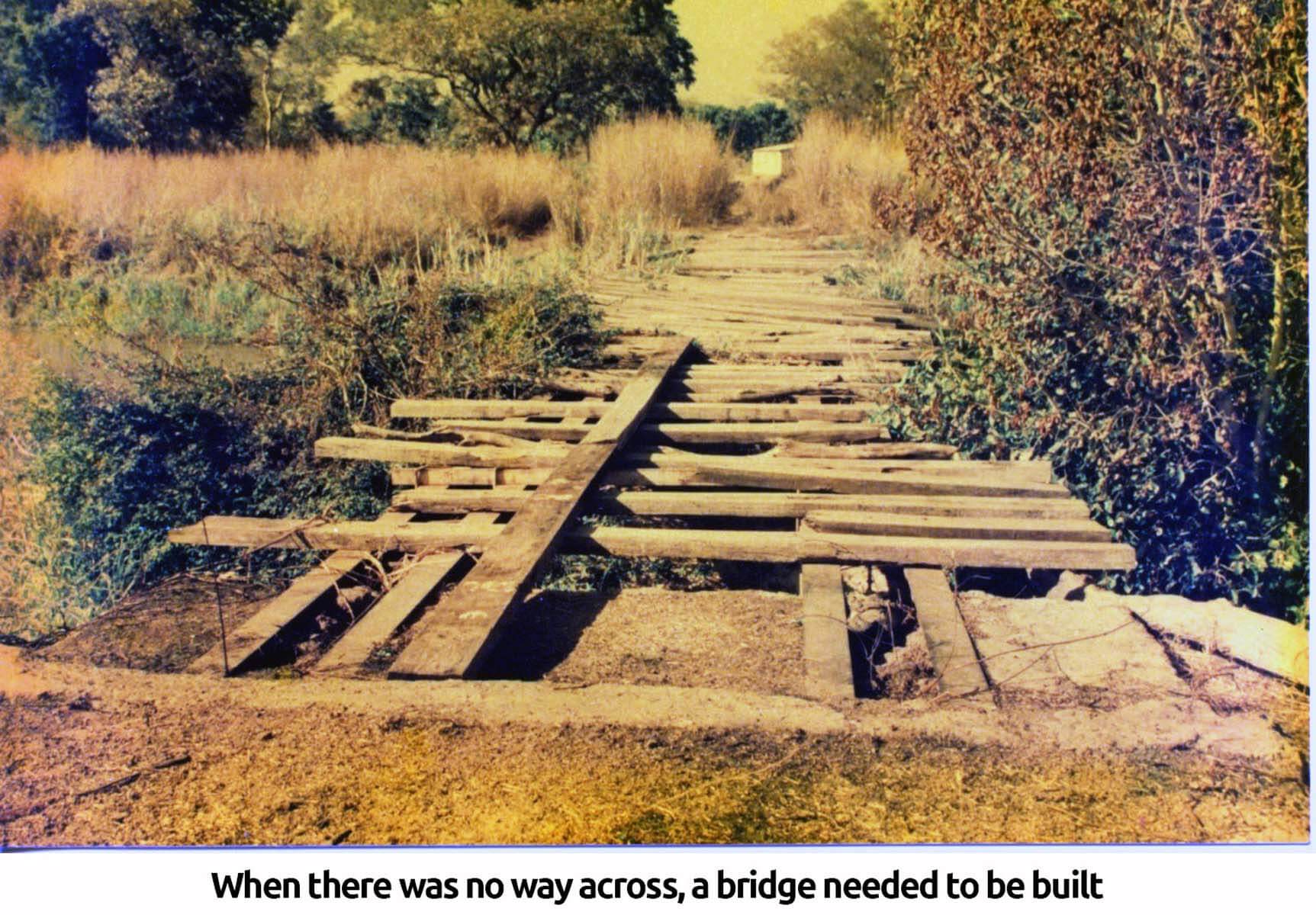

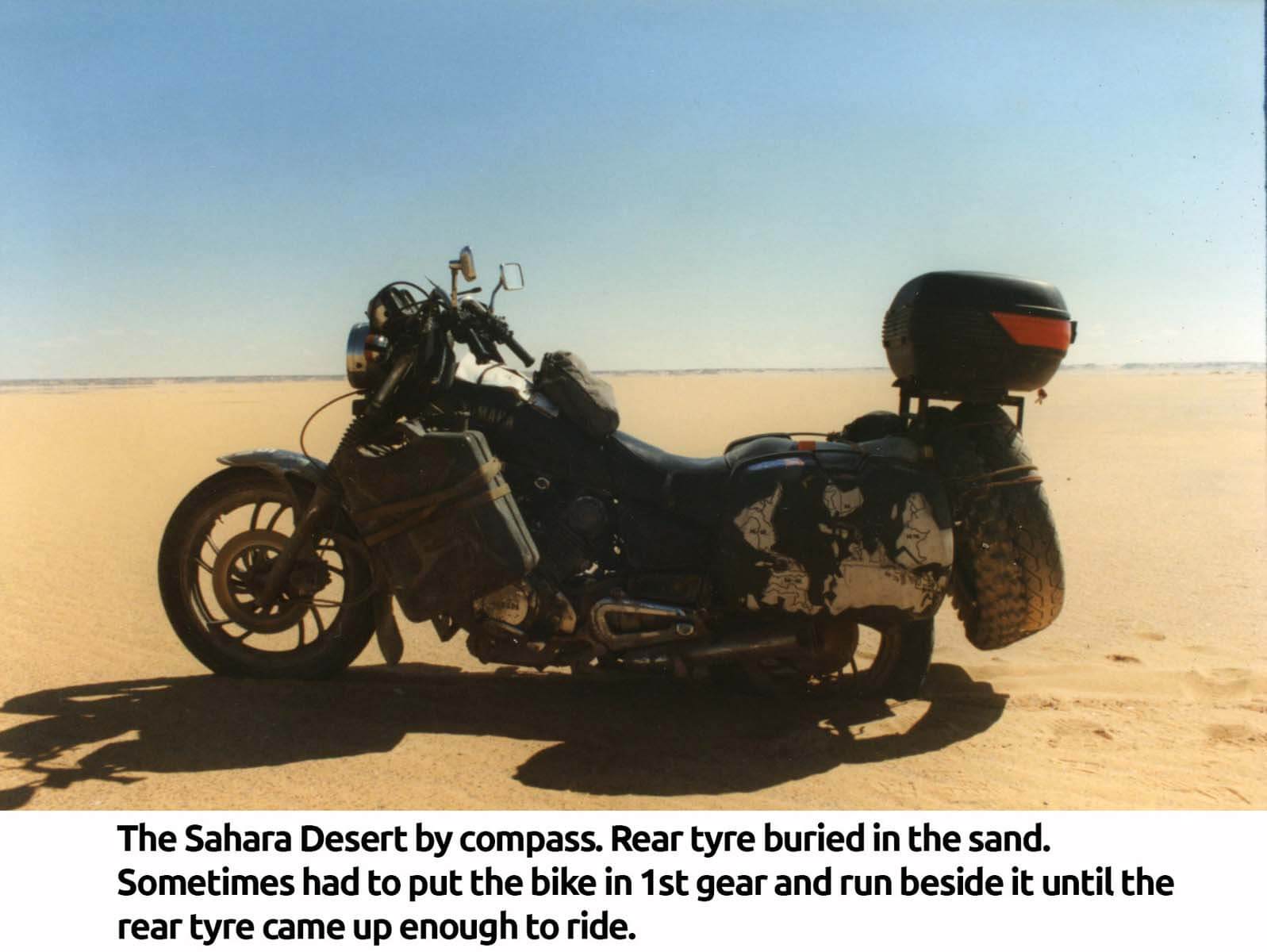

To reach her, Michael had to cross the Sahara Desert. "I travelled 800km by compass only—no track, no road markers. Massive sand dunes. The XV750 handled it all," he says. The following 4000km included just 400km of paved road. The rest was desert, bush, and jungle.

.

Amazingly, when Michael finally arrived in the remote township where his aunt was staying, he was greeted like a hero. "The townspeople were expecting me. Word had travelled ahead on the bush telegraph, and the roads were lined with people cheering."

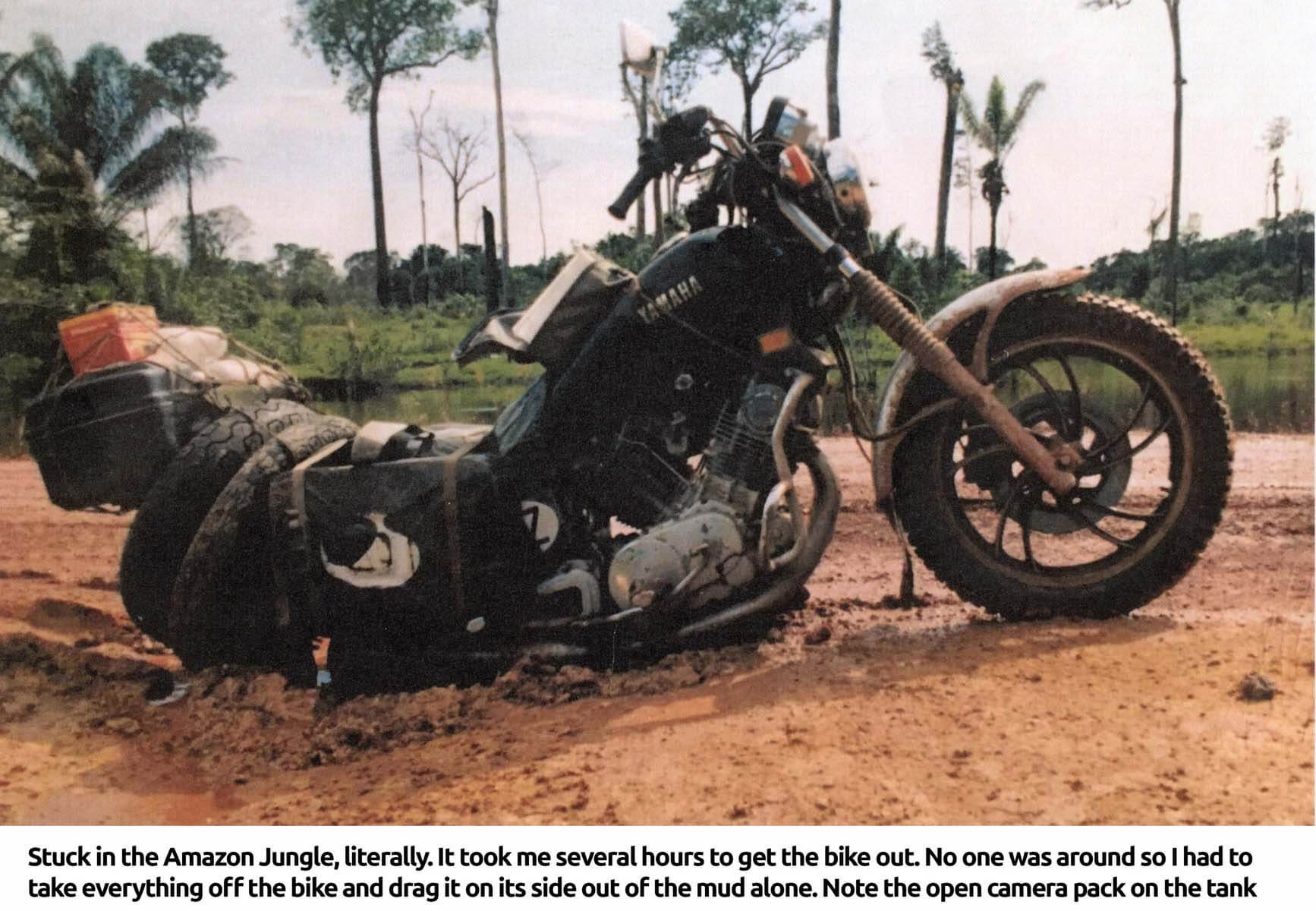

After reuniting with his aunt, Michael just kept riding. The XV750 took him from Khartoum to Cape Town, across to Australia, up to Alaska’s Arctic Ocean, and through every province in Canada and every state in the U.S.—except Hawaii. He explored Central America, Colombia, the Amazon Jungle, the Andes, and reached the southern tip of South America in Ushuaia.

He then looped back through India, Pakistan, and Iran—despite there being no road between the countries at the time. He even braved an Eastern European winter where temperatures plummeted to -24 degrees Celsius. "The snow on the back of the bike didn’t melt for three months," he says. "The bike was outside 24/7 and never seized up."

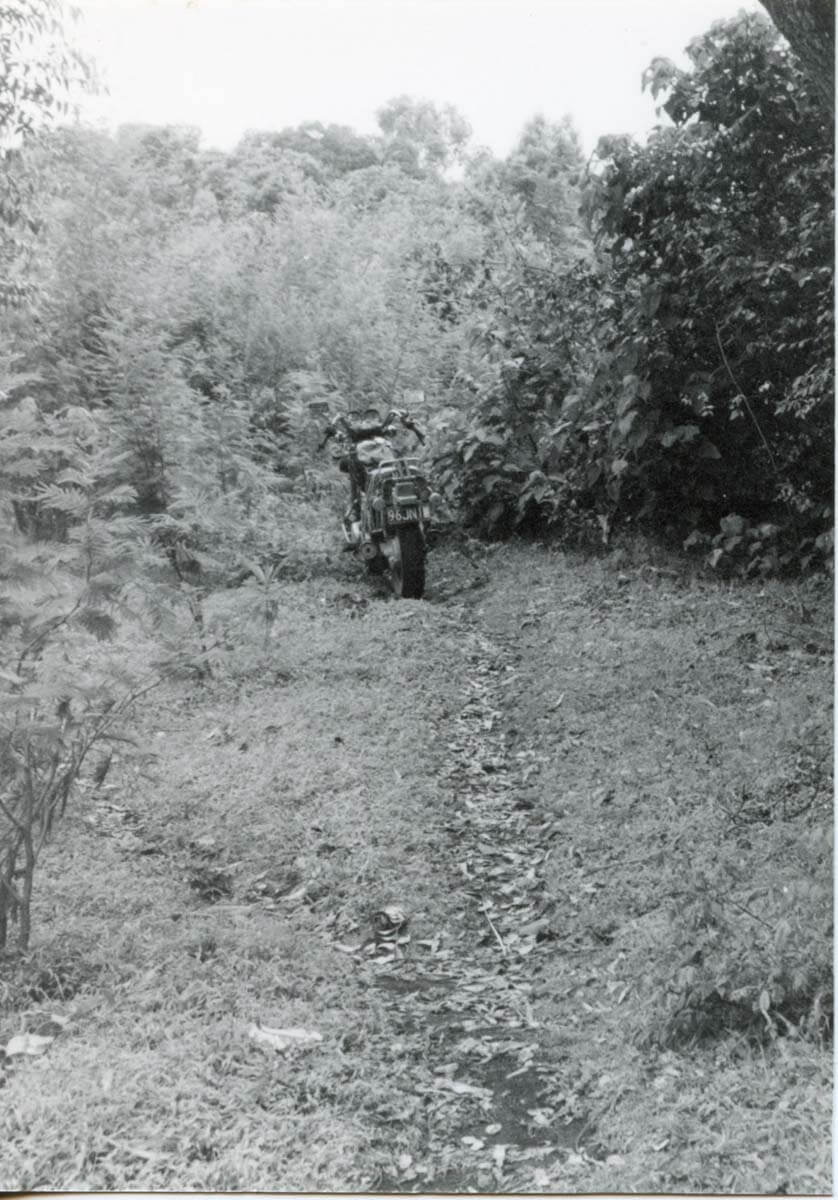

With fuel stops often up to 900 kilometres apart, his expanded 67-litre fuel tank was a necessity. "The bike’s best day was 1450km in the Atacama Desert in northern Chile—no roads," Michael remembers. "The worst day? Just 54km in the jungle of Sumatra."

He ran out of fuel only once—in the Central African Republic—when a trail marked on his map turned out not to exist. "I had no choice but to push on. When the fuel ran out, I walked a three-day round trip to get more."

Michael’s journey wasn’t without danger. In Syria, he was forced to play Russian roulette. In Mexico, a man jammed a gun into his stomach and demanded the bike. "I just refused to give it to him," Michael says. "Eventually, he lowered his gun and walked away."

In Peru, he was kidnapped by the Sendero Luminoso. "That took a bit of negotiation to resolve," he adds dryly.

The XV750 also refused to give up. Despite enduring some of the harshest terrain on Earth and more than 30 crashes, most of Michael’s XV750 remains original. "The gearbox, clutch, crankshaft—all engine internals except one set of pistons and rings—are original, as is the shaft drive and even the handlebars," he says. “Strangely enough, the starter motor on this model was meant to be a weak link, but mine never gave me any trouble, and that’s another original part still fitted.”

-

Maintenance was done roadside with Formula One-like efficiency. "Spark plugs in five minutes, tappet adjustment in 25, carburettors cleaned and back on in 90," he rattles off. Every 125,000km, he rewired the alternator to prevent burnout.

He changed the oil every 4000km and the oil filter every 8000km, a testament to the importance of regular maintenance.

Michael funded his travels creatively. "During my university years, I worked a few weeks each year packing kiwifruit," he says. "While travelling, I’d fly back home for a couple of months and work 100-hour weeks to bankroll another year on the road. I’d then fly to wherever I’d decided to ship the bike to while working, and would continue to adventure.”

He avoided cities and measured everything in litres of petrol. "Each day was different. I didn’t know if I’d do 50km or 500km. I’d just ride until sundown and find a place to pitch my tent."

One of the toughest days was Sumatra—12 hours of riding in the mud to cover just 54km. "Physical constraints slowed me down, not the bike," he says.

After returning to New Zealand, Michael got married, had four children in under four years, with a fifth nine years later, and found time to build a house. In 1995, he found time to ride 20,000km through the back roads of both islands of New Zealand in just 31 days. When the Midnight Special version of the XV750 was released, Michael briefly considered upgrading. "I flipped a coin 13 times. Every time it came up ‘keep the bike you have.’ The universe had spoken."

Today, he lives a quieter life in Katikati, still riding the same XV750 when time allows. Now 62, Michael reflects on his adventure with a grounded perspective. "If you’re going to do something, do it 100%. That’s what I did. I wouldn’t go to those extremes again but I had my adventure."

As for the XV750? It’s still there. Still running. Still being ridden by Michael whenever he has the time. “my son also drops by regularly to take it for a spin,” he adds.